by Peter Reiss

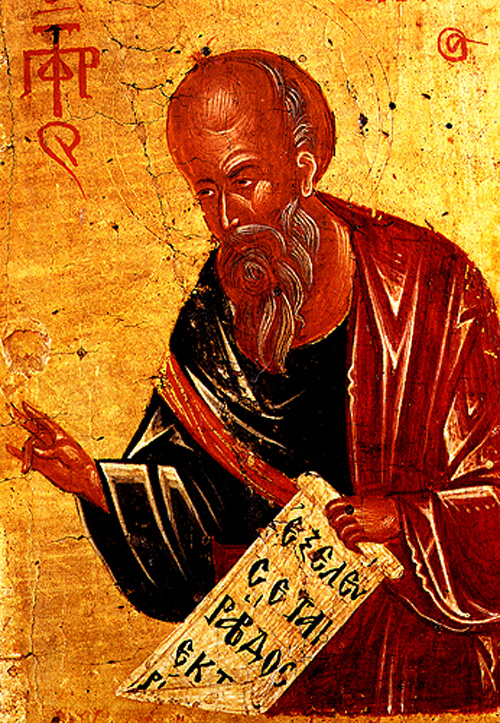

Prophet Elisha

Within the longer section of that part of 2 Kings in which Elisha is the stand-out figure against the various kings, there is a particular nest of two stories about the Aramean (Syrian) invaders. In 2 Kgs 6 they are out to get Elisha, but instead Elisha calls down a blindness on them, and the Syrian forces are captured and led by Elisha into Samaria. They are not killed (as the king suggests) but Elisha gives them a feast and they are sent home.

Next the Arameans besiege Samaria, there is horrific famine, but then the Aramean army think they can hear a large force attacking them and they flee from Samaria leaving their food for the hungry inhabitants.

The two stories are linked in 6:24 by a simple “some time later”; we are not told of the build-up to the siege, but we hear of its effects; the king is walking on the walls and is challenged by two mothers who have had to resort to eating their own children to survive (vv26-31). The King’s response is that he will have Elisha beheaded and so ends the encounter. The King continues along the walls and the two women disappear from the narrative even more abruptly than they appeared.

The narrator now takes us to the interaction between King and prophet and then on to the end of the siege.

These four victims (mothers and children) are without doubt victims of war, though several commentators suggest the behaviour of the mothers makes them criminal, reprehensible, less than human. We do not have their names, but commentators call them “cannibal mothers”. Victims are much more easily ignored if we avoid finding their name, and if we can label them as something different or bad. Refugees are nameless in the press – but we also come up with language which will diminish their humanity and highlight their difference. ‘Gas-lighting’ is one of the words of the moment. The children seldom get a mention at all.

If a victim does get to talk to someone in authority, it can still feel like talking from “down there” to “up there”. The king may engage in some sort of discussion but it is from the safety of the walls. The King is fasting but that is a chosen abstinence from food, not the situation the women are in. He will say, of course that he has been out and listened, but his reaction is not to help the women but to engage in violence against Elisha. The conversation is cut short and the women have no further chance. It should also be noted that Elisha and the elders are sitting in their house – are they as hungry as the women? are they concerned for the needier citizens? These questions are more pointed when we know that Elisha has a speciality in providing food when it is needed, and he has just arranged for a large feast for the Aramean soldiers. He has also raised the dead. Why can he not provide food for these women? It is I think fair to ask the question “Where was he?”

Within the narrative the two women are treated peremptorily by the king, and the prophet seems to be absent from the place of need. I suspect this is the experience of many survivors and victims.

But we should also look at ways in which the narrator potentially is part of the silencing, and how commentators have found other issues to focus on, and how easily we are led by narrators and commentators. The needs and suffering of these two women and the children are passed by, covered over.

Some commentators remind us that Deuteronomy 28 spells out what will happen to God’s people if they are disobedient. Among other things, judgement will include being besieged and that people will be reduced to eating their own children (28: 47-57). In 2 Kings 6 it is Samaria, but later the people of Jerusalem will be reduced to this when besieged by the Babylonians (see Lamentations). Commentators reflect on the judgement of God and the sinfulness of God’s people rather than the actual needs of these women.

Other commentators look instead at the longer story of God’s triumphing over the Arameans, the ways in which the people of Samaria are protected and saved because of and through Elisha. The king may despair, the king may have given up on leadership but Elisha will still point people to God’s answer. The bad Arameans are again sent packing! But if we are to applaud Elisha (and God) then surely we can also ask why they each / both allowed things to get as bad as they did. If Elisha / God had lifted the siege just a couple of days earlier the baby would have survived. We might be impressed by the quiet faith of Elisha who trusts that God will bring an outcome, but that does not mean we cannot ask why he was not pastorally more engaged.

A third focus of commentators is on the relationship and antagonism between King and prophet, and the narrator seems to think this important. For him the women are very minor characters as his focus is on king and prophet.

All three foci are alive and present in today’s world. Some find theological arguments / rationale to “explain” what has happened, a judgement of God; others want a more positive narrative in which there is victory, success, even if that means skirting round some inconvenient verses and situations. Many spend their energy and put their focus on the power battles between leaders, whether unions and the minister, bishop and government, or whatever. We can generate righteous indignation in our comments and contributions; of course the bigger issues are important, but it is noteworthy how the needs of the neediest get left out especially by those seeking to justify tougher measures, and those most zealous to prove a point. We can all get more energised by these debates than by the uncomfortable challenge that the two women put before us. The narrator allows these two needy victims to be written out, in favour of the successes of Elisha and the ongoing challenges of monarchy. They are not characters or people he wishes to follow up.

Some contrast this story with the “wisdom” of Solomon in 1 Kings 3 where Solomon adjudicates between two mothers and a surviving baby. Is the king in 2 Kings 6 failing in his kingship by being unable to make a judgement, or is the situation such that no king could make a judgement? The connection with 1 Kings 3 seems strong and it could be argued the two women in 1 kings 3 also are written out of the narrative once Solomon has shown his “wisdom”. In both cases then, the desperate needs of the women are ignored by the dominant narrative, just as the needs of the victims are so often written out of the dominant texts; I suspect this is not always deliberate, simply customary, we are taught to prioritise the argument and its justification.

One reason may be that the issues that the two women present, are so terrible and ones for which there is no easy solution. Like Job’s friends, solidarity in grieving is one response, but it takes time and leaders of all kinds are busy – they might do a quick walk on the walls to show they are in the real world, but they won’t stop for seven days in silent support; seven minutes would be uncomfortably long; and if a conversation is organised or even happens without planning, the leader is likely to use their power to cut it short; and like in this narrative the victim may struggle to get a second encounter though the King will proclaim that he has met the victims in authentic engagement.

Whether or not the narrator means us to reflect on Elisha sitting in his house with the elders, this brief narrative raises the uncomfortable question of the absence from the situation of this church leader; maybe he was deep in prayer, maybe waiting on God, but whatever, Elisha did not make time to find, listen to, or help these women.

Maybe the better way to read this difficult passage of the encounter of the King with the two women, is to freeze-frame at the point where the women share their story; don’t let the king rush off with his agenda; question the absence of the prophet; and stop the narrator from pushing on until we have decided what we could and should do in our world. Hear and hold fast to the testimony of the victims. Only then let the narrative resume.

Sadly no one heard these women – not the King, despite being present; not the prophet, who was not there; nor even the narrator who had a different story to tell; and readers have been so quick to condemn. Sadly these two women are not alone in being unheard and un-noticed.

Thank you, Peter. I remember hearing a woman preacher at my theological college – and her dismissal by one of the men as ‘hurt and strident’. The Church, sadly, is often no better at hearing voices that disturb our comfort than the wider world is. And often worse.

Thank you so much for this Peter, such a powerful reflection on this passage, which I had forgotten about.

I feel so seen and heard by what you wrote, it actually moved me to tears.

” it can still feel like talking from “down there” to “up there”. The king may engage in some sort of discussion but it is from the safety of the walls.” Yes! This is exactly what all my engagement with CofE safeguarding feels like.

And like the two women, I am judged and discarded.

All of this.

Thank you, if thank you is the right response.

What is maybe (even) more alarming, or just alarming in a different way, is that even the persistent lawyers like David Lammy and Martin Sewell cannot get access to the king and courtiers on the walls; their motion about the ISB (and NST) deemed not appropriate, thrown back down dismissively.

Peter, for the record, although you are far from being the first person to confuse me with the Labour MP for Tottenham), I’m David Lamming, not David Lammy!

David Lamming, my apologies for the mistake and my thanks for the work you do.

Really powerful reflection. Thank you!

I offer this testimony of a spiritual backdrop. One of the big denominations was engulfed in a prayerless “renewal” while another was in one of its more virulent “trendy” moments (I’m all for trendiness, except if it means forgetting to teach parishioners to pray for us).

With the likes of Savile arising, new state-trained teachers came to my secular school when I & my peers were 14 and asked leading questions to promote sex outside marriage without detailing how it could likely be at both parties’ expense, e.g predating & being preyed upon. (I didn’t speak, but I recognised from younger playground experience that the purpose was to make susceptible those boys who did answer up.)

We knew such things went on and that the world’s standards have always had ups & downs, but we believed it was the business of those involved and their families & chosen friends. An older class tore a strip off a teacher for inserting himself in pupils’ essentially private affairs and earnestly pretending to be “one of us” when we were capable of holding more balanced conversations in our own playground. (The separate biology lesson was fine.)

At the time, the intuitive wisdom of the young in applying time-honoured principles astutely, was trampled upon. The head of department who coordinated these sessions, left after carrying on with a boy. That was apparently around the time from when girls & women mostly stopped feeling able to signal to a boy / man how she was to be related to, because the swing away from stuffiness had gone too far & too thoughtlessly (and without rectifying unequal pay). Now look at all of today’s billions of the lonely and frightened, in many countries, of whatever sex, age or inclination.

Lately I have run this by christians I bumped into (mostly married and senior volunteers), all of whom normalised it by saying schools had “always” staged these “discussions” or denying that they ever have, and / or said “it’s the Fall”. No, it isn’t “the Fall”. It was the lack of alertness in caring for the nations’ youth in prayer (because secular authorities don’t listen to moralising), at a particular time when I was there.

God knew we needed a sexual revolution, environment revolution, charismatic revolution, media revolution, etc; but a couple of our main religions were too absorbed in manoeuvres around their image, or giving the green light to sectarian sophistries, rather than distinctly underpinning us by the supplication St Paul enjoins; meanwhile abroad has seen the rise of materialistic moralisers.

Thus some christians now risk prolonging the complacency towards those more vulnerable than themselves, and high-handedly gaslighting (word used without apology) a young eyewitness. Toying with consciences already toyed with. God knew we would live on a rough planet and it’s no use christians triumphally superseding a provident Saviour just because the world is now modern.