Ever since Paul described the Christian path as resembling a race, Christians have found the image of movement and journey to describe their lives a helpful one. The Pilgrim’s Progress is perhaps the classic description of the nature of the Christian life, a journey with set-backs as well as periods of encouragement and grounds for hope. The activity of pilgrimage itself is a metaphor for the whole of the Christian life. Any pilgrim who has travelled on foot, whether to Canterbury or Compostela in Spain, will know the combination of pain and expectation and joy as the journey comes to an end. Christian living itself combines the periods of doubt with moments of insight and breakthrough. As with pilgrimage the Christian is given the grace to persevere through ‘cloud and sunshine’.

It is on reflection a puzzle to discover that large numbers of Christians appear to reject the notion of pilgrimage in favour of a faith that puts a stress on arriving at their destination on the day of their conversion. For many evangelical Christians the decisive moment in their lives is the experience of giving their hearts and loyalty to Christ so that he is said to be the Lord and Master of their lives. Simultaneously they are promised infallible access to his guiding word in the text of Scripture. The task from then on is to hold themselves safe from falling away so that when the moment of death comes they may be transported to glory. The entire Christian journey seems to have been accomplished in a moment of time and the only place that seems possible to travel to is backwards to perdition. That would involve a loss of the salvation so preciously gained at the moment when the individual became a Christian. Staying in this place of conversion is an activity not totally without tension or even fear.

This way of being a Christian contrasts starkly with the way of pilgrimage that we outlined at the beginning. It will be clear which way I prefer from the tone of my writing. But I want to make it clear that what I have said about the evangelical/conversionist path is not meant to imply that it is entirely wrong. The experience of conversion may be totally self-authenticating and valid for the person concerned. The problem for me is not the moment of conversion but what happens afterwards that is the issue. The new Christian, because he/she has received everything on the first day of the journey seems to have nowhere else to go, nothing else to explore. They are stuck in a place of supposed fulfilment and joy but which, in reality, seems to be a place of stagnation and what appears to be sterility. Chris has often spoken to me about the loud music that accompanies the worship of evangelical Christians who want to tell the world about the joy of conversion. Somehow I suspect the music is loud because it enables them to bypass the activity of having to think about what comes next in their Christian lives. I have listened (painfully sometimes) to numerous testimonies given by Christians which record their moments of conversion. Listening to these accounts critically, two things stand out. The first thing is that the structure of conversion experiences is very similar wherever you hear it. While the details of time and place will obviously be unique, the formula of words is almost identical in every case. The second thing that is striking is that normally nothing to match the conversion experience has happened since. It is as though the Christian has been up a mountain, seen a glimpse of glory but has never been able to evoke anything like it again.

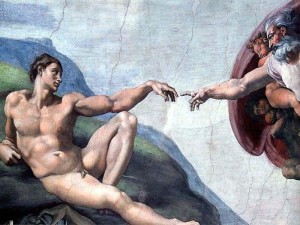

The liberal or progressive Christian, were they to give a testimony, would give a very different story. Not for them in all probability was there a bright light on the Damascus road. Maybe they would happier with the language of a series of flashes along the road. None of these experiences of light was on its own sufficient to convince totally but when seen together over a period of time, the progressive Christian had been able to discern a pattern, a pattern which speaks of God. The word that describes this way of conversion is perhaps a pilgrim faith. The pilgrim Christian is the one who travels, sometimes alone, sometimes with others along a path which he has decided is one he wants to follow. It leads to a destination that he wants to call truth or reality but she/he knows that until he arrives the full shape and glory of the destination will not be known. As I have said in previous posts, the pilgrim Christian travels with this combination of faith and hope in what is fully to be revealed.

Why do I commend to my reader the way of the pilgrim Christian? It certainly describes my own path but that is not the main reason for commending it. Look back over my life-time I can see that the path of the pilgrim Christian has given me the freedom and the excitement to explore and discover the transcendent in many manifestations. It is this combination of freedom and the excitement of a constant possibility of discovery that I want to commend. This is not the time for personal autobiography except to say that being a pilgrim has given me the permission to travel and discover aspects of truth within a variety of cultures and belief systems. It has been and still is an exciting journey and I suspect that God is not far from most human beings who seek him whether or not they are Christian. By travelling with others who may not even speak my language or engage with my culture I may nevertheless find God in that journey. Each new discovery, each new insight shows me beyond all doubt that anything I do know already is incomplete. The fullness of truth, the depth of reality is always beyond and further along the road but as a pilgrim I can continue to travel towards them.