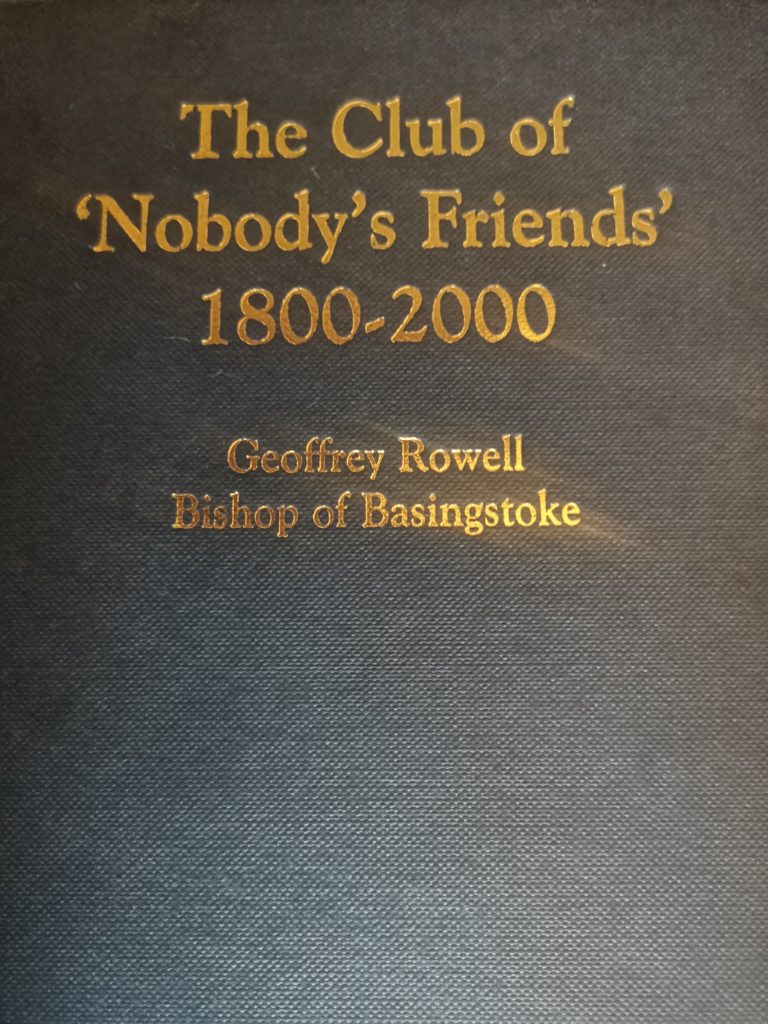

I was recently given a copy of Nobody’s

Friends 1800-2000, a biography and historical diary of the Lambeth Palace dining

club which featured in the Peter Ball hearings at IICSA. It emerged at the

Inquiry that Lord Lloyd of Berwick had cited their mutual membership of the

secretive club to Archbishop Carey in one of many ‘letters of influence’ in

support of Ball. Nobody’s Friends is a gathering which quietly fosters

establishment links between church and Westminster (mostly the Tory bits of it)

and meets in the Guards Room at Lambeth Palace. Newly elected members ‘justify’

themselves during congratulatory speeches which honour any advancement in the

various pecking orders (episcopal, judicial, political) of its members. It

undoubtedly offers a fulcrum of patronage to any senior cleric lucky enough to

be elected member, who might aspire to a mitre.

Membership has included many bishops and archbishops, headmasters from a sprinkling of top schools, various Archbishop’s Appointments Secretaries, Prime Minister’s Appointments Secretaries, Leaders of the House of Commons and House of Lords, Tory peers, Admiralty figures, judicial figures and church lawyers. Such heavyweights as Sir Michael Havers (later Lord Chancellor), Lord Pym, Douglas Hurd, Lord Justice Bingham (former Master of the Rolls) have graced its tables. Several of the senior clerics on the board of Ecclesiastical have also enjoyed membership, and one of the headmaster directors of the church’s insurer. The current club President is believed to be Sir Philip Mawer, who was on the directors board of Ecclesiastical when he was also at same time Secretary General of Synod.

Jonathan Fletcher, Archbishop Welby’s friend and a regular participant at the Iwerne camps from the early 1950s has been a member since 1983. His father, Lord Fletcher, was also a member. The club seems to have had a culture of nepotism in which the scion of ennobled members themselves become elected members.

But another name kept ringing bells. Sir William Van Straubenzee, Tory minister in Northern Ireland under Heath and later a prominent Synod member and Church Estates Commissioner, became a member in 1973. In 1988 he was elected Vice President of the club, and in 1991 elected President of Nobody’s – a position he held until his death in 1999. Clearly very well connected, his London home was a grace-and-favour apartment in Lambeth Palace in the Lollard’s Tower. This pied-à-terre gave name to a group of Tory wets, the Lollards, who met there during Thatcher’s premiership.

Straubenzee was cited in government files in relation to abuse at the Kincora boys home in Belfast. Sir Anthony Duff sent an MI5 dossier on Straubenzee to Sir Robert Armstrong (now Lord Armstrong) in 1986. Kincora may have have been run under the watchful eye of the secret services who used it as a ‘dirty tricks’ blackmail operation, although the findings of the Hart report (Northern Ireland Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry HIA Inquiry 2014-2016) disputed this. The involvement of MI5 in Kincora has never meaningfully been investigated. And although three men who shared in the running of the home were prosecuted and jailed in the 1980s – figures from the political and establishment worlds named in connection with the abuse and trafficking of boys from this and other homes in Belfast did not face questioning.

Armstrong himself was also a member of Nobody’s from 1984, and may be still as far as anyone knows. It’s unlikely that other members had awareness at the time when the senior mandarin from Number 10 received this intelligence from MI5. Armstrong appears to have remained tight-lipped, although it is recorded that these files were passed to the Prime Minister. So two men, one of whom had grounds from the security services to suspect possible abuse activities by the other – both toasted the club’s customs and membership alongside assorted archbishops during coffee and mint thins. It’s a disconcerting image.

Equally as disconcerting, there seems to be no indication that the Church of England shared this information with IICSA. Nor following the Peter Wanless and Richard Whittam QC Review when the material from the Cabinet Office first came to public light in 2015 after their report.

Despite judicial interest in these matters, the suffering of victims and survivors, and the need for transparency – the Church of England did not seem to offer this information to these inquiries? Presumably many current Nobody’s Friends, including many bishops, have copies of this rare publication. It did not occur to any of them, nor to the club Treasurer, that this might be helpful information – not least because it might shed light on the culture of protectionism afforded by these private clubs.

Another Lambeth Palace dining club offers a deeper picture of privilege and protection. In 1993 a former chairman of the Nikaean Club and head of Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge went to court for abusing a boy between the ages of 14 and 16. Canon (later Bishop) Christopher Hill, also a member of the Nikæan Club, accompanied Patrick Gilbert to court. Gilbert was also able to brandish a character witness letter from another Nikaean member – former Archbishop of Canterbury, Donald Coggan. Gilbert, who was also secretary of the wine committee at The Athenaeum, admitted a previous conviction for indecent assault on two 13-year-old school boys in 1962. Despite this and despite the seriousness of the charge, and almost certainly owing to the protecting influence of a Lambeth Palace dining club, he received a suspended sentence and sympathy from the judge for the considerable stress he had endured. As the judge explained, he decided not to jail the bachelor because of his health and ‘very severe punishment’ he had already undergone through loss of reputation. Both Hill and Coggan were also members of The Athenaeum. It’s not who you know… but who you dine with.

Returning to Nobody’s it is oddly disturbing that its members are likely to have their own copies of this book, and many older members will remember Straubenzee as President of the club. They will have presumably been aware of media reports in recent years of the mention of Straubenzee in secret service reports to the Cabinet Office.

A culture of ‘say nothing unless asked’ is a culture still reluctant to move on from subtle complicity and subterfuge. This mindset has already led to the current existential crisis of the bishops and senior ‘management’ of the Church. The time for keeping of secrets Luca Brasi-style to protect the reputation of a Lambeth Palace eliterie should long be over. The Church should no longer entertain disposition to this kind of omerta. A church with secrecy riven in its bones is not a church with a healthy and redemptive future. It is hardly worth the candle.

Incidentally I was interested to find that two senior figures I had told of my abuse – were both members. Stephen Platten, former Bishop of Wakefield, and John Eastaugh, former Bishop of Hereford.

With no little irony, I give the last

word of this essay to Lord Lloyd. When questioned at the Inquiry, his

description of Nobody’s Friends was that it was a “perfectly ordinary dining

club”.

Gilo

CoEditor, Letters to a Broken Church (Ekklesia 2019)