Over the years I have had more than a passing interest in church architecture. One of the interesting things is to interpret why churches are built and furnished in different ways. There are of course, major differences between churches built in the eastern Mediterranean and those which have been designed in the West. One obvious feature in Eastern Orthodox churches which is different from what we are used to, is the way that there is almost a complete absence of windows in such buildings. In many cases the walls are filled with paintings or mosaics, and the only way we can see them is from the light that comes from artificial light, especially candles. The interaction between flickering candles and mosaics is fairly magical, and we would add mysterious. This sense of mystery, a participation in the unknown, is exactly what Eastern architect wanted to evoke in the worshippers.

Over the years I have had more than a passing interest in church architecture. One of the interesting things is to interpret why churches are built and furnished in different ways. There are of course, major differences between churches built in the eastern Mediterranean and those which have been designed in the West. One obvious feature in Eastern Orthodox churches which is different from what we are used to, is the way that there is almost a complete absence of windows in such buildings. In many cases the walls are filled with paintings or mosaics, and the only way we can see them is from the light that comes from artificial light, especially candles. The interaction between flickering candles and mosaics is fairly magical, and we would add mysterious. This sense of mystery, a participation in the unknown, is exactly what Eastern architect wanted to evoke in the worshippers.

In the western half of Christendom we observe a major transition between the mediaeval period and what came later. In some churches of the Reformation that wanted to downplay the prominence that had been given to the old Roman rite or the Mass, there was an emphasis on the pulpit and thus it was situated in a place of prominence at the centre of the building. The reading and the preaching about the Word of God were clearly the most important activities in church buildings of this tradition. Most of the churches in the Anglican tradition still gave a prominence to the altar and it was and is important for traditional Anglican worship that this structure should be visible from every part of the building. But even here, elaborate and intrusive pulpits were frequently constructed in the 18th century to emphasise the place of preaching in these buildings. Most of these were however, swept away by the Victorians. In most Anglican churches we now have forward facing pews so that there is once more a focus on the altar and the communion services that took place there.

Today in some churches there is a new architectural phenomenon to be seen. This is the raising of a stage construction at the front of the church. The purpose of this is not for the preaching of the word or the reading of the Bible but it is to give a platform for new servants of the church, the music group. The churches where services can last for over two hours, at least half of that time is spent in listening to this music group performing, or perhaps accompanying congregational singing. This music, to judge by the amount of time spent on its performance, has become the most important feature of worship in many modern churches. From the perspective of view of a traditional leader of worship such as myself, I have to ask the question as to whether such musical performance is entertainment rather than real worship. Are people coming to church, at least on occasion, simply to be entertained? Are worshippers turning into an audience? This is a valid question which I feel we need to consider. If I am right, then there has been a devaluation of the activity of worship.

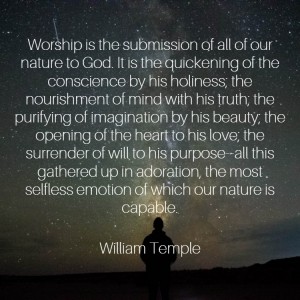

What is worship? This is a question we have to address in order to give a measured response to our questions. Most traditional answers to this question would be to see worship as what the people of God bring as their offering to him. The emphasis is here, not on what we receive in church, but on what we can give. Traditional liturgical words like offertory and thanksgiving imply that the people in a congregation are expected to do something, to put an effort into this activity of worship. The traditional procession of the elements of bread and wine together with the envelopes containing financial gifts represent an important symbolism at the heart of worship. We can sum up the whole movement of the service by saying that worship is what we come to give of ourselves to God so that he can give himself to us in the form of consecrated bread and wine. This initial giving of ourselves makes possible the receiving of the gift of Christ so that ‘we can dwell in him and he in us’.

From the perspective of this kind of theology, there is something very superficial and inadequate about an endless succession of Christian songs being performed on a stage. Even if this kind of music is agreeable to a worshipper, and often it is not, it is hard to see how listening even to a semi-professional band is spiritually edifying. If in fact listening to this music is mainly to be regarded as entertainment, it is difficult to see how it becomes any kind of offering to God. It could of course be argued that the offerings of professional cathedral choirs are also forms of entertainment, but there are some major differences. Most composers of such liturgical music, such as Palestrina or Bach, have a very strong sense of the meaning of the words that they set to music. In other words each composer is interpreting a traditional liturgical text and giving it a distinct musical form. The words of the liturgy, in summary, are given a musical interpretation which heightens their meaning and impact on those who listen. Words and music achieve a harmony which can enrich the worshipper and become part of their offering to God.

To return to my title and question about worship. Are congregations sometimes becoming more like audiences and consumers of something that is being performed on a stage? Is the act of worship becoming closer to an attendance at the theatre? If entertainment were to become the dominant emphasis experienced by congregations, then we would be moving away from the old notion that we go to church to make our offering of praise and thanksgiving. When we say the traditional words ‘it is meet and right, our duty and our joy in every place and at all times to give you thanks O God’, we are saying something quite different from ‘I go to church because I enjoy listening to a musical performance’. Perhaps the next time we go to a church we need to look around at the architecture. The placing of a stage at the front of a church building may speak to us as powerfully as the positioning of the altar or the pulpit in the past. Is the church architecture encouraging us to think of ourselves as consumers of musical entertainment or are we being called to give thanks and offer ourselves in the worship of Almighty God?