A document which I hope will always be referred to as the Blackburn Letter appeared yesterday June 17th 2019. It is written by the senior staff of the Blackburn Diocese and is addressed to their licensed staff, clergy and Readers, and safeguarding officers. In essence, it is commending study of the recent IICSA report on the Diocese of Chichester and the Peter Ball case. Those of us who have been cheering on the case of safeguarding for some time cannot but feel that this is progress. The Letter may claim historic importance because it shows that in one diocese of the Church of England a group of senior church people really seem to understand all the dimensions of safeguarding in the Church. They understand it in a way that goes far beyond the box-ticking reputational management process which is what safeguarding comes to be in many places.

Why am I personally moved by this letter? For a start, the Blackburn senior staff want those who study the IICSA report to notice before anything else the suffering that has been caused by sexual abuse to real victims. Many people, including myself, have always pleaded that safeguarding should start at this end – the needs of survivors. Sexual abuse, however many years ago it took place is a ‘human catastrophe’ for those caught up in it as victims as well as causing ‘lifelong impact’. How right that the Blackburn Letter begins with words from Psalm 51. ‘Have mercy on us O God, for we have sinned’. The letter makes no apology for putting the human suffering endured by survivors right at the beginning. The traditional preoccupation of the Church, reputation management, only gets a mention in para 5. It is mentioned, but only as a way of explaining that it has been a factor in not dealing well with allegations from the past. When protecting the good name of the institution has taken precedence, the suffering of survivors has been made far worse.

Moving on from what appear to be genuine expressions of sorrow and contrition on behalf of the whole Church, the letter begins to explore what can be done in the future. The congregations are to be places where ‘children and vulnerable adults can be entirely safe’ but also where ‘the voices of those who have difficult things to say or disclosures to make are heard and acted on.’ The second part of this wish is far harder to deliver. Many survivors report that the reason the Church has found it so hard to deal with their needs is because the recounting of their past experience of suffering causes so much discomfort in the hearer. None of us find it easy to listen to stories of abuse, particularly when the abuser was a trusted figure, like a priest or a bishop. Taking on board the idea that a member of the home team is an abuser is deeply unsettling. It is far easier to shut down the discordant thought and that is what many people will do in practice.

A further insight in the letter, which is music to my ears, is the recognition that clericalism, deference and abuse of power lie behind the ‘cover-up’ and the silencing of the ‘voices of the vulnerable’. Clergy and other leaders have power within the relationships they possess and there needs to be ‘deeper awareness’ of that power. This theme of ministerial power and its potential for harm is the topic that I have chosen to reflect on in the forthcoming volume of essays Letters to a Broken Church. There is so much more to be said on this topic.

I want to make two further observations about the letter. One is that the letter appears to have been written at a visceral level. In short, the emotions of sorrow and repentance are allowed to rise to the surface and be dominant themes in what is communicated. Somehow the letter, assisted by a quotation from Andrew Graystone’s essay of a week ago, manages to avoid completely the somewhat petulant tone of so many expressions of ‘regret’ and ‘apology’ that we associate with official statements. Are we correct in seeing in this letter the beginning of something new, a combination of deep sorrow and genuine feeling for the needs of survivors and those wronged by the Church? Such sentiments, if they are followed through, will begin to meet the needs of survivors. It may be the beginning of the ‘change of culture’ that has been looked for by so many. It is also the first sign that some senior clergy individually and corporately are beginning to ‘get it’.

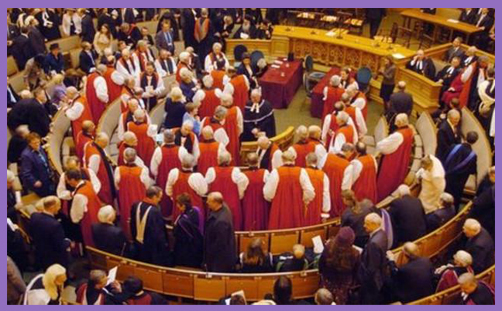

My final observation is a somewhat irreverent one but it needs to be made. Is it a coincidence that this remarkable statement of unanimity and contrition about safeguarding emerges from a diocese that is far away from London? The Diocese of Blackburn may be articulating a somewhat prophetic position precisely because it feels itself geographically and in other ways remote from the centres of Anglican influence represented by Church House and Lambeth Palace respectively. The prospect of an entire diocese studying the articulate comments and criticisms of the Independent Inquiry must be causing considerable discomfort among those who try hard to control the narrative and set the agenda for the Church of England. The forthcoming debates at York General Synod may or may not get to the heart of the issue as the Blackburn Letter seems to have done. Whatever is said at York, the effect of the process of study in the Blackburn diocese will have implications which will reverberate long into the future. It will be increasingly hard to claim that no one understands the issues. The consequences of this serious reflective study on safeguarding and the needs of survivors will be hard to limit only to one circumscribed geographical area represented by the Diocese of Blackburn.

Right at the heart of this blog’s concern and many other places is the desire that the suffering of abuse survivors should be understood, responded to and healed. Up till now the Church has often insisted of responding through damage limitation and avoidance. The Blackburn response is suggesting that these methods are no longer viable. Perhaps the Blackburn Letter is the beginning of a new phase in the history of the Church of England. One day it may be said that that on the 17th June 2019 the Church of England, represented by the Diocese of Blackburn, began to move from denial and avoidance of the issue of abuse victims to a stance resembling healing, humility and new beginnings.